Arabic calligraphy, known for its elegance and complexity, is a profound art form that intertwines language, culture, and spirituality. As a visual representation of the Arabic script, it encompasses both an artistic and technical mastery that has evolved over centuries. This article delves into the rich history, essential knowledge, and practices surrounding Arabic calligraphy, exploring how it has become a symbol of cultural identity and artistic expression.

Historical Background

Origins and Early Development

The origins of Arabic calligraphy trace back to the early days of Islam. The Arabic script itself emerged in the 4th century CE, evolving from the Nabataean script, which was used in the Arabian Peninsula. However, it wasn’t until the advent of Islam in the 7th century that Arabic calligraphy began to flourish as an art form.

The Quran, the holy book of Islam, played a pivotal role in the development of Arabic calligraphy. Early manuscripts of the Quran were written in a script known as Kufic, which is characterized by its angular and geometric shapes. Kufic script was predominantly used during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods and was favored for its clarity and formality in religious texts.

Classical Period

The classical period of Arabic calligraphy began around the 9th century with the introduction of the Hijazi and Naskh scripts. The Hijazi script, derived from the earlier Kufic, was more cursive and fluid, while the Naskh script became popular due to its readability and ease of use in copying texts. The Naskh script gained prominence during the Abbasid Caliphate and has since remained one of the most widely used scripts in Arabic calligraphy.

The 10th century marked the beginning of the golden age of Arabic calligraphy. During this period, calligraphers began to develop a range of styles and techniques, leading to the creation of highly intricate and decorative scripts. Notable calligraphers like Ibn Muqla and Ibn al-Bawwab made significant contributions by establishing fundamental principles of proportion and alignment that are still followed today.

The Ottoman Influence

The Ottoman Empire, spanning from the 14th to the early 20th centuries, had a profound impact on Arabic calligraphy. Ottoman calligraphers refined existing scripts and developed new styles, such as the Diwani and Thuluth. The Diwani script, known for its ornate and flowing lines, was used primarily for official documents and court correspondence. The Thuluth script, with its large and elegant letters, was often used for architectural inscriptions and decorative purposes.

During the Ottoman period, calligraphy schools were established, and calligraphers were highly esteemed. The art form was closely associated with the cultural and religious life of the empire, with calligraphers often serving as advisors and scholars.

Knowledge and Skills

The Scripts

Arabic calligraphy encompasses several distinct scripts, each with its own characteristics and uses. Understanding these scripts is fundamental for any aspiring calligrapher:

- Kufic: Known for its geometric and angular appearance, Kufic script is often used in decorative contexts, such as on architectural elements and mosaics. It is one of the oldest forms of Arabic calligraphy and serves as a basis for many modern scripts.

- Naskh: This script is praised for its legibility and simplicity, making it ideal for printed text and everyday writing. Its smooth, flowing lines contrast with the rigid structure of Kufic script.

- Thuluth: Thuluth is recognized for its large, elegant letters and is often used in architectural inscriptions and titles. It requires a high level of skill due to its complex shapes and fluidity.

- Diwani: Developed during the Ottoman era, the Diwani script is known for its intricate, decorative style. It is commonly used in official documents and artistic compositions.

- Ruqa’a: A more casual script, Ruqa’a is used for everyday writing and has a more straightforward, rounded appearance.

Calligraphic Tools and Techniques

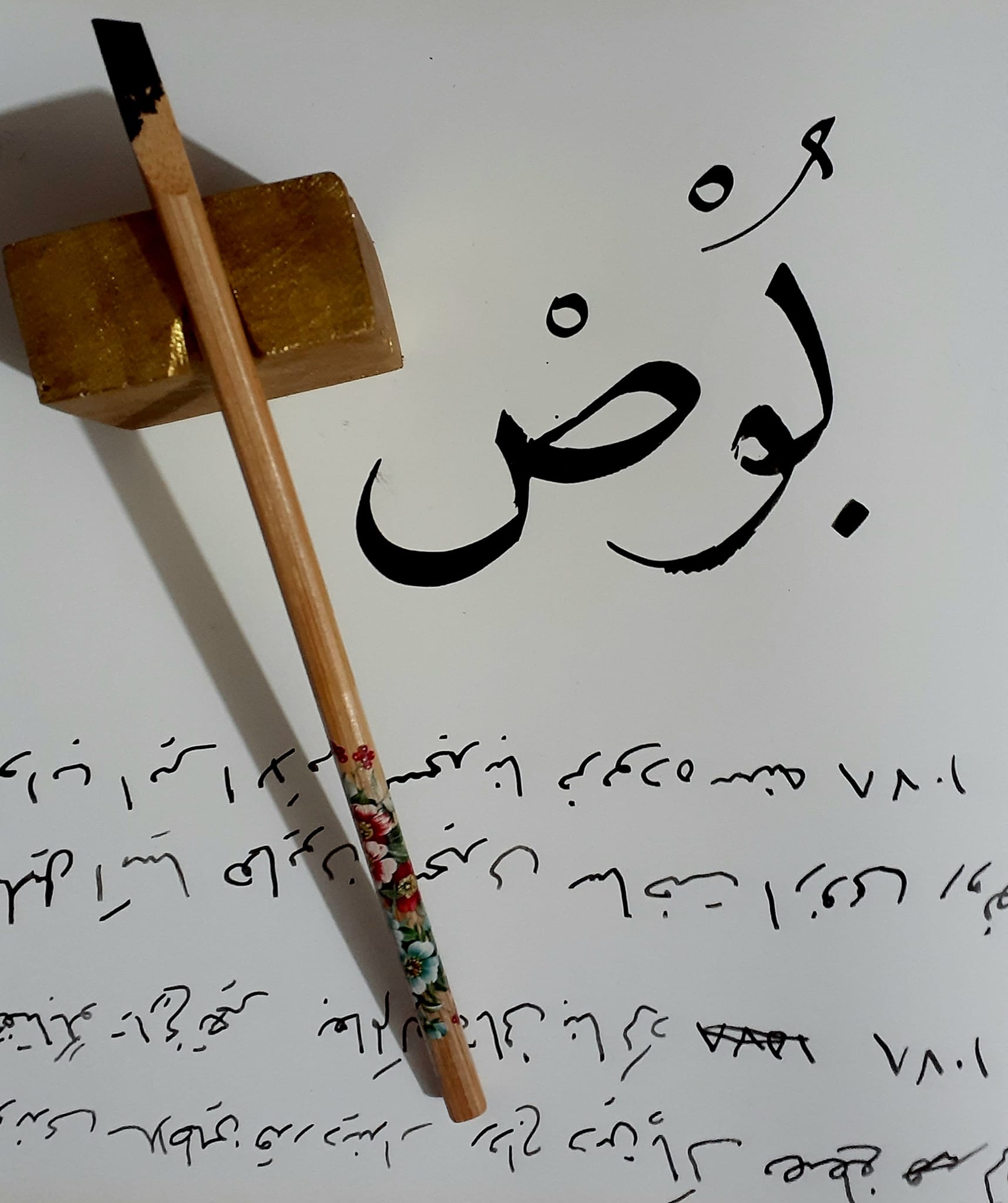

Mastery of Arabic calligraphy involves both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Calligraphers use a variety of tools and techniques to create their art:

- Pen (Qalam): The traditional calligraphy pen is made from a reed or bamboo and is cut at an angle to create different strokes. The quality of the pen affects the precision and style of the calligraphy.

- Ink (Miqta): Calligraphers use special ink made from natural materials. The ink’s consistency and color can influence the final appearance of the calligraphy.

- Paper and Surfaces: Calligraphy is traditionally practiced on paper or parchment, but modern calligraphers may also use canvas, wood, or fabric. The choice of surface affects the texture and finish of the calligraphy.

- Practice and Precision: Achieving proficiency in Arabic calligraphy requires extensive practice and attention to detail. Calligraphers must master various strokes, spacing, and alignment to produce harmonious and aesthetically pleasing work.

Practices and Contemporary Relevance

Artistic Expression

Arabic calligraphy is more than a means of writing; it is a form of artistic expression that reflects the calligrapher’s personal style and creativity. Modern calligraphers often experiment with traditional scripts, blending them with contemporary designs to create innovative artworks.

Contemporary Arabic calligraphy frequently incorporates abstract elements and modern design principles, bridging the gap between traditional craftsmanship and modern aesthetics. This evolution allows calligraphy to remain relevant and appealing in today’s artistic landscape.

Cultural and Religious Significance

Arabic calligraphy holds profound cultural and religious significance. In the Islamic tradition, calligraphy is seen as a form of worship and devotion, reflecting the beauty and majesty of the Quranic text. Many calligraphers view their work as a spiritual practice, aiming to convey the divine message through their art.

Calligraphy is also a key element of Islamic art and architecture. It adorns mosques, palaces, and public spaces, serving both decorative and educational purposes. The use of calligraphy in these contexts underscores its importance in conveying religious and cultural values.

Education and Preservation

The preservation and transmission of Arabic calligraphy are crucial for maintaining its legacy. Calligraphy schools and workshops around the world continue to teach traditional techniques and foster new generations of calligraphers. Institutions like the Istanbul Calligraphy Museum and the Arab Calligraphy Centre in Cairo play a vital role in preserving historical manuscripts and promoting the art form.

Digital technology has also impacted Arabic calligraphy, with digital tools enabling calligraphers to experiment with new styles and techniques. While this innovation offers new opportunities, it is essential to balance technology with traditional practices to preserve the essence of the art form.

Global Influence

Arabic calligraphy has transcended regional boundaries and influenced art and design globally. Its intricate patterns and elegant forms have inspired artists and designers worldwide, leading to a fusion of cultures and styles. Exhibitions, workshops, and collaborations continue to showcase the beauty and versatility of Arabic calligraphy, contributing to its global appreciation.

Conclusion

Arabic calligraphy is a rich and dynamic art form that reflects the history, culture, and spirituality of the Arabic-speaking world. Its evolution from early Kufic scripts to contemporary expressions highlights the art form’s enduring significance and adaptability. Through its intricate scripts, calligraphic tools, and artistic practices, Arabic calligraphy continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the globe.

By understanding the historical context, mastering the essential skills, and embracing both traditional and modern practices, calligraphers can contribute to the ongoing legacy of this remarkable art form. Arabic calligraphy not only preserves the beauty of the written word but also celebrates the profound connection between language, art, and culture.